Spirodelabase

Duckweeds are ideal material for physiological, biochemical, and genomic studies because of their direct contact with medium, rapid growth and relatively small genome sizes. They are valuable for bio-manufacturing through genetic engineering technology. Progress in duckweed-based commercial products can be easily maintained by vegetative reproduction in aseptic cultivation for decades. The small size of the plant is ideal for maintaining diverse accessions and therefore ideal for DNA-level evolutionary studies. Some species, such as Lemna minor, are used by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for measuring water quality; their growth rates are sensitive to a wide range of environmental contaminants such as metals, nitrates, and phosphates. Rapid growth also offers practical applications of duckweeds as a biofuel crop.

The Spirodela Polyrhiza (Greater Duckweed) Genome v3.1 has been sequenced by using 454 with 20X coverage and the assembly was of very high quality improved by FPC. 20 chromosome-aligned sequences and a pseudomolecule 0 containing all unsorted and short sequences. The map-based genome sequence of Spirodela polyrhiza aligned with its chromosomes, a reference for karyotype evolution by Cao, Hieu; Vu, Giang; Wang, Wenqin; Appenroth, Klaus; Messing, Joachim; Schubert, Ingo. New Phytologist, 2015.

Protocols

Protocols of Growing Duckweeds (PDF)

Protocol of total genomic DNA isolation from duckweeds with CTAB (PDF)

Protocol of DNA barcode duckweeds by atpF-atpH marker (PDF)

External Links

Page Components

Background:

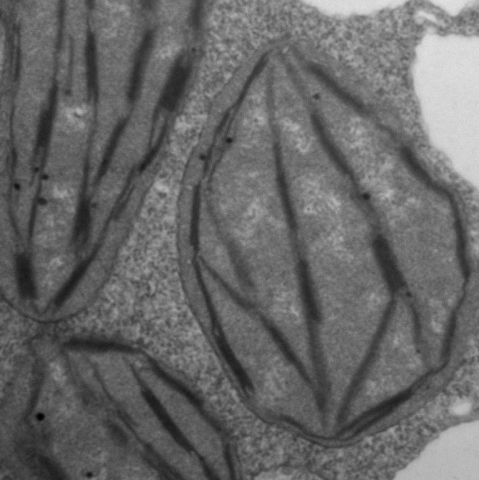

Chloroplast genomes provide a wealth of information for evolutionary and population genetic studies. Chloroplasts play a particularly important role in the adaption for aquatic plants because they float on water and their major surface is exposed continuously to sunlight. The subfamily of Lemnoideae represents such a collection of aquatic species that because of photosynthesis represents one of the fastest growing plant species on earth.

Methods:

We sequenced the chloroplast genomes from three different genera of Lemnoideae, Spirodela polyrhiza, Wolffiella lingulata and Wolffia australiana by high-throughput DNA sequencing of genomic DNA using the SOLiD platform. Unfractionated total DNA contains high copies of plastid DNA so that sequences from the nucleus and mitochondria can easily be filtered computationally. Remaining sequence reads were assembled into contiguous sequences (contigs) using SOLiD software tools. Contigs were mapped to a reference genome of Lemna minor and gaps, selected by PCR, were sequenced on the ABI3730xl platform.

Conclusions:

This combinatorial approach yielded whole genomic contiguous sequences in a cost-effective manner. Over 1,000-time coverage of chloroplast from total DNA were reached by the SOLiD platform in a single spot on a quadrant slide without purification. Comparative analysis indicated that the chloroplast genome was conserved in gene number and organization with respect to the reference genome of L. minor. However, higher nucleotide substitution, abundant deletions and insertions occurred in non-coding regions of these genomes, indicating a greater genomic dynamics than expected from the comparison of other related species in the Pooideae. Noticeably, there was no transition bias over transversion in Lemnoideae. The data should have immediate applications in evolutionary biology and plant taxonomy with increased resolution and statistical power.

Duckweed Chloroplast

The Spirodela polyrhiza genome reveals insights into its neotenous reduction fast growth and aquatic lifestyle.

Wang W, Haberer G, Gundlach H, Gläßer C, Nussbaumer T, Luo MC, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M, Kerstetter RA, Shanklin J, Byrant DW, Mockler TC, Appenroth KJ, Grimwood J, Jenkins J, Chow J, Choi C, Adam C, Cao XH, Fuchs J, Schubert I, Rokhsar D, Schmutz J, Michael TP, Mayer KF, Messing J. The Spirodela polyrhiza genome reveals insights into its neotenous reduction fast growth and aquatic lifestyle. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3311.

Abstract

The subfamily of the Lemnoideae belongs to a different order than other monocotyledonous species that have been sequenced and comprises aquatic plants that grow rapidly on the water surface. Here we select Spirodela polyrhiza for whole-genome sequencing. We show that Spirodela has a genome with no signs of recent retrotranspositions but signatures of two ancient whole-genome duplications, possibly 95 million years ago (mya), older than those in Arabidopsis and rice. Its genome has only 19,623 predicted protein-coding genes, which is 28% less than the dicotyledonous Arabidopsis thaliana and 50% less than monocotyledonous rice. We propose that at least in part, the neotenous reduction of these aquatic plants is based on readjusted copy numbers of promoters and repressors of the juvenile-to-adult transition. The Spirodela genome, along with its unique biology and physiology, will stimulate new insights into environmental adaptation, ecology, evolution and plant development, and will be instrumental for future bioenergy applications.

Evolution of Genome Size in Duckweeds (Lemnaceae)

Wang W, Kerstetter R, Michael T. Evolution of genome size in duckweeds (Lemnaceae). Journal of Botany. 2011.

Abstract

To extensively estimate the DNA content and to provide a basic reference for duckweed genome sequence research, the nuclear DNA content for 115 different accessions of 23 duckweed species was measured by flow cytometry (FCM) stained with propidium iodide as DNA stain. The 1C-value of DNA content in duckweed family varied nearly thirteen-fold, ranging from 150 megabases (Mbp) in Spirodela polyrhiza to 1,881 Mbp in Wolffia arrhiza. There is a continuous increase of DNA content in Spirodela, Landoltia, Lemna, Wolffiella, and Wolffia that parallels a morphological reduction in size. There is a significant intraspecific variation in the genus Lemna. However, no such variation was found in other studied species with multiple accessions of genera Spirodela, Landoltia, Wolffiella, and Wolffia.

The mitochondrial genome of an aquatic plant, Spirodela polyrhiza.

Wang W, Wu Y, Messing J. The mitochondrial genome of an aquatic plant, Spirodela polyrhiza. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46747. Epub 2012 Oct 4.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Spirodela polyrhiza is a species of the order Alismatales, which represent the basal lineage of monocots with more ancestral features than the Poales. Its complete sequence of the mitochondrial (mt) genome could provide clues for the understanding of the evolution of mt genomes in plant.

METHODS:

Spirodela polyrhiza mt genome was sequenced from total genomic DNA without physical separation of chloroplast and nuclear DNA using the SOLiD platform. Using a genome copy number sensitive assembly algorithm, the mt genome was successfully assembled. Gap closure and accuracy was determined with PCR products sequenced with the dideoxy method.

CONCLUSIONS:

This is the most compact monocot mitochondrial genome with 228,493 bp. A total of 57 genes encode 35 known proteins, 3 ribosomal RNAs, and 19 tRNAs that recognize 15 amino acids. There are about 600 RNA editing sites predicted and three lineage specific protein-coding-gene losses. The mitochondrial genes, pseudogenes, and other hypothetical genes (ORFs) cover 71,783 bp (31.0%) of the genome. Imported plastid DNA accounts for an additional 9,295 bp (4.1%) of the mitochondrial DNA. Absence of transposable element sequences suggests that very few nuclear sequences have migrated into Spirodela mtDNA. Phylogenetic analysis of conserved protein-coding genes suggests that Spirodela shares the common ancestor with other monocots, but there is no obvious synteny between Spirodelaand rice mtDNAs. After eliminating genes, introns, ORFs, and plastid-derived DNA, nearly four-fifths of the Spirodela mitochondrial genome is of unknown origin and function. Although it contains a similar chloroplast DNA content and range of RNA editing as other monocots, it is void of nuclear insertions, active gene loss, and comprises large regions of sequences of unknown origin in non-coding regions. Moreover, the lack of synteny with known mitochondrial genomic sequences shed new light on the early evolution of monocot mitochondrial genomes.

Analysis of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase expression during turion formation induced by abscisic acid in Spirodela polyrhiza (greater duckweed).

Wang, W, Messing J. Analysis of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase expression during turion formation induced by abscisic acid in Spirodela polyrhiza (greater duckweed). BMC Plant Biol. 2012 Jan 11;12:5.

Abstract

Aquatic plants differ in their development from terrestrial plants in their morphology and physiology, but little is known about the molecular basis of the major phases of their life cycle. Interestingly, in place of seeds of terrestrial plants their dormant phase is represented by turions, which circumvents sexual reproduction. However, like seeds turions provide energy storage for starting the next growing season.

High-Throughput Sequencing of Three Lemnoideae (Duckweeds) Chloroplast Genomes from Total DNA

Wang W, Messing J. High-Throughput Sequencing of Three Lemnoideae (Duckweeds) Chloroplast Genomes from Total DNA. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24670. Epub 2011 Sep 9.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Chloroplast genomes provide a wealth of information for evolutionary and population genetic studies. Chloroplasts play a particularly important role in the adaption for aquatic plants because they float on water and their major surface is exposed continuously to sunlight. The subfamily of Lemnoideae represents such a collection of aquatic species that because of photosynthesis represents one of the fastest growing plant species on earth.

METHODS:

We sequenced the chloroplast genomes from three different genera of Lemnoideae, Spirodela polyrhiza, Wolffiella lingulata and Wolffia australiana by high-throughput DNA sequencing of genomic DNA using the SOLiD platform. Unfractionated total DNA contains high copies of plastid DNA so that sequences from the nucleus and mitochondria can easily be filtered computationally. Remaining sequence reads were assembled into contiguous sequences (contigs) using SOLiD software tools. Contigs were mapped to a reference genome of Lemna minor and gaps, selected by PCR, were sequenced on the ABI3730xl platform.

CONCLUSIONS:

This combinatorial approach yielded whole genomic contiguous sequences in a cost-effective manner. Over 1,000-time coverage of chloroplast from total DNA were reached by the SOLiD platform in a single spot on a quadrant slide without purification. Comparative analysis indicated that the chloroplast genome was conserved in gene number and organization with respect to the reference genome of L. minor. However, higher nucleotide substitution, abundant deletions and insertions occurred in non-coding regions of these genomes, indicating a greater genomic dynamics than expected from the comparison of other related species in the Pooideae. Noticeably, there was no transition bias over transversion in Lemnoideae. The data should have immediate applications in evolutionary biology and plant taxonomy with increased resolution and statistical power.

DNA barcoding of the Lemnaceae, a family of aquatic monocots.

Wang W, Wu Y, Yan Y, Ermakova M, Kerstetter R, Messing J. DNA barcoding of the Lemnaceae, a family of aquatic monocots. BMC Plant Biol. 2010 Sep 16;10:205.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Members of the aquatic monocot family Lemnaceae (commonly called duckweeds) represent the smallest and fastest growing flowering plants. Their highly reduced morphology and infrequent flowering result in a dearth of characters for distinguishing between the nearly 38 species that exhibit these tiny, closely-related and often morphologically similar features within the same family of plants.

RESULTS:

We developed a simple and rapid DNA-based molecular identification system for the Lemnaceae based on sequence polymorphisms. We compared the barcoding potential of the seven plastid-markers proposed by the CBOL (Consortium for the Barcode of Life) plant-working group to discriminate species within the land plants in 97 accessions representing 31 species from the family of Lemnaceae. A Lemnaceae-specific set of PCR and sequencing primers were designed for four plastid coding genes (rpoB, rpoC1, rbcL and matK) and three noncoding spacers (atpF-atpH, psbK-psbI and trnH-psbA) based on the Lemna minor chloroplast genome sequence. We assessed the ease of amplification and sequencing for these markers, examined the extent of the barcoding gap between intra- and inter-specific variation by pairwise distances, evaluated successful identifications based on direct sequence comparison of the "best close match" and the construction of a phylogenetic tree.

CONCLUSIONS:

Based on its reliable amplification, straightforward sequence alignment, and rates of DNA variation between species and within species, we propose that the atpF-atpH noncoding spacer could serve as a universal DNA barcoding marker for species-level identification of duckweeds.